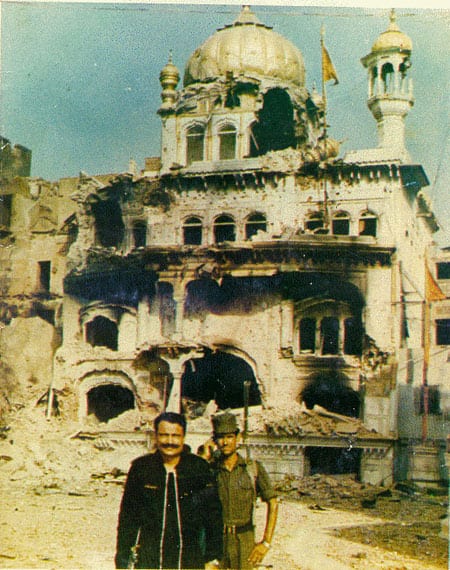

![Indira Gandhi Lunched oppressive operations against many minorities]()

Indira Gandhi Lunched oppressive operations against many minorities

Nowhere else in the world did the year 1984 fulfill its apocalyptic portents as it did in India. Separatist violence in the Punjab, the military attack on the great Sikh temple of Amritsar; the assassination of the Prime Minister, Mrs. Indira Gandhi; riots in several cities; the gas disaster in Bhopal – the events followed relentlessly on each other. There were days in 1984 when it took courage to open the New Delhi papers in the morning.

Of the year’s many catastrophes, the sectarian violence following Mrs Gandhi’s death had the greatest effect on my life. Looking back, I see that the experiences of that period were profoundly important to my development as a writer; so much so that I have never attempted to write about them until now.

At that time, I was living in a part of New Delhi called Defence Colony – a neighborhood of large, labyrinthine houses, with little self-contained warrens of servants’ rooms tucked away on roof-tops and above garages. When I lived there, those rooms had come to house a floating population of the young and straitened journalists, copywriters, minor executives, and university people like myself. We battened upon this wealthy enclave like mites in a honeycomb, spreading from rooftop to rooftop. Our ramshackle lives curtailed from our landlords of chiffon-draped washing lines and thickets of TV serials.

I was twenty-eight. The city I considered home was Calcutta, but New Delhi was where I had spent all my adult life except for a few years in England and Egypt. I had returned to India two years before, upon completing a doctorate at Oxford, and recently found a teaching job at Delhi University. But it was in the privacy of my baking rooftop hutch that my real life was lived. I was writing my first novel, in the classic fashion, perched in garret.

On the morning of October 31, the day of Mrs. Gandhi’s death, I caught a bus to Delhi University, as usual, at about half past nine. From where I lived, it took an hour and half; a long commute, but not an exceptional one for New Delhi. The assassination had occurred shortly before, just a few miles away, but I had no knowledge of this when I boarded the bus. Nor did I notice anything untoward at any point during the ninety-minute journey. But the news, traveling by word of mouth, raced my bus to the university.

When I walked into the grounds, I saw not the usual boisterous, Frisbee-throwing crowd of students but a small group of people standing intently around transistor radio. A young man detached himself from one of the huddles and approached me, his mouth twisted into light tipped, knowing smile that seems always to accompany the gambit “Have you heard…?”

The campus was humming, he said. No one knew for sure, but it was being said that Mrs. Gandhi had been shot. The word was that she had been assassinated by two Sikh bodyguards, in revenge for her having sent troops to raid the Sikhs’ Golden Temple in Amritsar earlier that year.

Just before stepping into the lecture room, I heard a report on All India Radio, the national network: Mrs. Gandhi had been rushed to hospital after her attempted assassinations.

Nothing stopped: the momentum of the daily routine carried things forward. I went into a classroom and began my lecture, but not many students had shown up and those who had were distracted and distant; there was a lot of fidgeting.

Halfway through the class, I looked out through the room’s single, slit-like window. The sunlight lay bright on the lawn below and on the trees beyond. It was the time of year when Delhi was at its best, crisp and cool. Its abundant greenery freshly watered by the recently retreated monsoons, its skies washed sparkling clean. By the time I turned back, I had forgotten what I was saying and had to reach for my notes.

My unsteadiness surprised me. I was not an uncritical admirer of Mrs. Gandhi. Her brief period of semi-dictatorial rule in the mid-seventies was still alive in my memory.

The first reliable report of Mrs. Gandhi’s death was broadcast from Karachi, by Pakistan, at around 1:30 PM. On All India Radio regular broadcast had been replaced by music.

I left the university in the late afternoon with a friend, Hari Sen, who lived at the other end of the city. I needed to make a long-distance call, and he had offered to let me use his family telephone.

To get to Hari’s house we had to change buses at Connaught Place, that elegant circular arcade that lies at the geographical heart of Delhi, linking the old city with the new. As the bus swung around the periphery of the arcade, I noticed that the shops, stalls, and eteries were beginning to shut down, even though it was still afternoon.

Our next bus was not quite full, which was unusual. Just as it was pulling out, a man ran out of the office and jumped on. He was middle-aged and dressed in shirt and trousers, evidently an employee in one of the government buildings. He was a Sikh, but I scarcely noticed this at the time.

He probably jumped on without giving the matter any thought, this being his regular, daily bus. But, as it happened, on this day no choice could have been more unfortunate, for the route of the bus went past the hospital where Indira Gandhi’s body then lay. Certain loyalists in her party had begun inciting the crowds gathered there to seek revenge. The motorcade of Giani Zail Singh, the President of the Republic, a Sikh, had already been attacked by a mob.

None of this was known to us then, and we would never have suspected it: violence had never been directed at the Sikhs in Delhi.

As the bus made its way down New Delhi’s broad, tree-lined avenues, official-looking cars, with outriders and escorts, overtook us, speeding toward the hospital. As we drew nearer, it became evident that a large number of people had gathered there. But this was no ordinary crowd: it seemed to consist of red-eyed young men in half-buttoned shirts. It was now that I noticed that my Sikh fellow-passenger was showing signs of anxiety, sometimes standing up to look out, sometimes glancing out the door. It was too late to get off the bus; thugs were everywhere.

The bands of young men grew more and more menacing as we approached the hospital. There was a watchfulness about them; some were armed with steel rods and bicycle chains; others had fanned out across the busy road and were stopping cars and buses.

A stout woman in sari sitting across aisle from me was the first to understand what was going on. Rising to her feet, she gestured urgently at the Sikh, who was sitting hunched in his seat. She hissed at him in Hindi, telling him to get down and keep out of sight.

The man started in surprise and squeezed himself into the narrow footspace between the seats. Minutes later, our bus was intercepted by a group of young men dressed in bright, sharp synthetics. Several had bicycle chains wrapped around their wrists. They ran along beside the bus as it slowed to a halt. We heard them call out to the driver through the open door, asking if there were any Sikhs in the bus.

The driver shook his head. No, he said, there were no Sikhs in the bus.

A few rows ahead of me, the crouching turbaned figure had gone completely still.

Outside, some of the young men were jumping up to look through the windows, asking if there were any Sikhs in the bus. There was no anger in their voices; that was the most chilling thing of all.

No, someone said, and immediately other voices picked up the refrain. Soon all the passengers were shaking their heads and saying, no, no, let us go now, we have to get home.

Eventually, the thugs stepped back and waved us through.

Nobody said a word as we sped away down Ring Road.

Hari Sen lived in one of New Delhi’s recently developed residential colonies. It was called Safdarjang Enclave, and it was neatly and solidly middle-class, a neighborhood of aspirations rather than opulence. Like most such suburbs, the area had a mixed population: Sikhs were well represented.

A long street ran from end to end of the neighborhood, like the spine of a comb, with parallel side streets running off it. Hari lived at the end of one of those streets, in a fairly typical, big, one-storey bunglow. The house next door, however, was much grander and uncharacteristically daring in design. An angular structure, it was perched rakishly on stilts. Mr. Bawa, the owner, was an elderly Sikh who had spent a long time abroad, working with various international organizations. For several years, he had resided in Southeast Asia; thus the stilts.

Hari lived with his family in a household so large and eccentric that it had come to be known among his friends as Macondo, after Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s magical village. On this occasion, however, only his mother and teenage sister were at home. I decided to stay over.

It was a bright morning. When I stepped into the sunshine, I came upon a sight that I could never have imagined. In every direction, columns of smoke rose slowly into a limpid sky. Sikh houses and businesses were burning. The fires were so carefully targeted that they created an effect quite different from that of a general conflagration: it was like looking upward into the vault of some vast pillared hall.

The columns of smoke increased in number even as I stood outside watching. Some fires were burning a short distance away. I spoke to a passerby and learned that several nearby Sikh houses had been looted and set on fire that morning. The mob had started at the far end of the colony and was working its way in our direction. Hindus or Muslims who had sheltered Sikhs were also being attacked; their houses too were being looted and burned.

It was still and quite, eerily so. The usual sounds of rush-hour traffic were absent. But every so often we heard a speeding car or a motorcycle on the main street. Later, we discovered that these mysterious speeding vehicles were instrumental in directing the carnage that was taking place. Protected by certain politicians, “organizers” were zooming around the city, assembling the mobs and transporting them to Sikh-owned houses and shops.

Apparently, the transportation was provided free. A civil-rights report published shortly afterward stated that this phase of violence “began with the arrival of groups of armed people in tempo vans, scooters, motorcycles or trucks,” and went on to say,

With cans of petrol they went around the localities and systematically set fire to Sikh-houses, shops and Gurdwaras…the targets were primarily young Sikhs. They were dragged out, beaten up and then burned alive…In all the affected spots, a calculated attempt to terrorize the people was evident in the common tendency among the assailants to burn alive Sikhs on public roads.

Fire was everywhere; it was the day’s motif. Throughout the city, Sikh houses were being looted and then set on fire, often with their occupants still inside.

A survivor – a woman who lost her husband and three sons – offered the following account to Veena Das, a Delhi sociologist:

Some people, the neighbors, one of my relatives, said it would be better if we hid in an abandoned house nearby. So my husband took our three sons and hid there. We locked the house from outside, but there was treachery in people’s hearts. Someone must have told the crowd. They baited him to come out. Then they poured kerosene on that house. They burnt them alive. When I went there that night, the bodies of my sons were on the loft – huddled together.

Over the next few days, some 2,500 people died in Delhi alone. Thousands more died in other cities. The total death toll will never be known. The dead were overwhelmingly Sikh men. Entire neighborhoods were gutted; tens of thousands of people were left homeless.

Like many other members of my generation, I grew up believing that mass slaughter of the kind that accompanied the Partition of India and Pakistan, in 1947, could never happen again. But that morning in the city of Delhi, the violence had reached the same level of intensity.

As Hari and I stood staring into the smoke-streaked sky, Mrs. Sen, Hari’s mother, was thinking of matters closer at hand. She was about fifty, a tall, graceful woman with a gentle, soft-spoken manner. In an understated way, she was also deeply religious, a devout Hindu. When she heard what was happening, she picked up the phone and called Mr. And Mrs. Bawa, the elderly Sikh couple next door, to let them know that they were welcome to come over. She met with unexpected response: an awkward silence. Mrs. Bawa thought she was joking, and wasn’t sure whether to be amused or not.

Toward midday, Mrs. Sen received a phone call: the mob was now in the immediate neighborhood, advancing systematically from street to street. Hari decided that it was time to go over and have a talk with the Bawas. I went along.

Mr. Bawa proved to be small, slight man. Although he was casually dressed, his turban was neatly tied and his beard was carefully combed and bound. He was puzzled by our visit. After a polite greeting, he asked what he could do for us. It fell to Hari to explain.

Mr. Bawa had heard about Indira’s assassination, of course, and he knew there had been some trouble. But he could not understand why these “disturbances” should impinge on him or his wife. Not only was his commitment to India and the Indian state absolute but it was evident from his bearing that he belonged to the country’s ruling elite.

How do you explain to someone who has spent a lifetime cocooned in privilege that a potentially terminal rent has appeared in the wrappings? We found ourselves faltering. Mr. Bawa could not bring himself to believe that a mob might attack him.

By the time we left, it was Mr. Bawa who was mouthing reassurances. He sent us off with jovial pats on our backs. He did not actually say “Buck up”, but his manner said it for him.

We were confident that the government would soon act to stop the violence. In India, there is a drill associated with civil disturbances: a curfew is declared; paramilitary units are deployed; in extreme cases the army marches to the stricken areas. No city in India is better equipped to perform this drill than New Delhi, with its huge security apparatus. We learned later that in some cities – Calcutta, for example, the state authorities did act promptly to prevent violence. But in New Delhi – and much of North India – [days] followed without a response.

Every few minutes we turned to the radio, hoping to hear that the Army had been ordered out. All we heard was mournful music and descriptions of Mrs. Gandhi’s lying in state; of coming and goings of dignitaries, foreign and national. The bulletins could have been messages from another planet.

As the afternoon progressed, we continued to hear reports of the mob’s steady advance. Before long, it had reached the next alley: we could hear the voices; the smoke was everywhere. There was still no sign of Army or police.

Hari again called Mr. Bawa, and now the flames visible from his windows, he was more receptive. He agreed to come over with his wife, just for a short while. But there was a problem: How? The two properties were separated by a shoulder -high wall, so it was impossible to walk from one house to the other except along the street.

I spotted a few thugs already at the end of the street. We could hear the occasional motorcycle, cruising slowly up and down. The Bawas could not risk stepping out in the street. They would be seen: the sun had dipped low in the sky, but it was still light. Mr. Bawa balked at the thought of climbing over the wall: it seemed an inseparable obstacle at his age. But eventually Hari persuaded him to try.

We went to wait for them at the back of the Sen’s house – in a spot that was well sheltered from the street. The mob seemed terrifyingly close, the Bawas reckless in their tardiness. A long time appeared before the elderly couple finally appeared, hurrying towards us.

Mr. Bawa had changed before leaving the house: he was neatly dressed, dapper, even a blazer and cravat. Mrs. Bawa dressed in salwar and kameez. Their cook was with them, and it was with his assistance that they made it over the wall. The cook, who was Hindu, then returned to the house to stand guard.

Hari led the Bawas into the drawing room, where Mrs. Sen was waiting dressed in chiffon sari. The room was large and well appointed, its walls hung with a rare and beautiful set of miniatures. With the curtains now drawn and the lamps lit, it was warm and welcoming. But all that lay between us and the mob in the street was a row of curtained French windows and a garden wall.

Mrs. Sen greeted the elderly couple with folded hands as they came in. The three seated themselves in the intimate circle, and soon a silver tea tray appeared. Instantly, all constraint evaporated, and, to the tinkling of porcelain, the conversation turned to the staples of New Delhi drawing-room chatter.

I could not bring myself to sit down. I stood in the corridor, distracted, looking outside through the front entrance.

A couple of scouts on motorcycles had drawn up next door. They had dismounted and were inspecting the house, walking in among the concrete stilts, looking up into the house. Somehow, they got wind of the cook’s presence and called him out.

The cook was very frightened. He was surrounded by thugs thrusting knives in his face and shouting questions. It was dark, and some were carrying kerosene torches. Wasn’t it true, they shouted, that his employers were Sikhs.

Where were they? Were they hiding inside? Who owned the house – Hindus or Sikhs? Hari and I hid behind the wall and listened to the interrogation. Our fates depended on this lone, frightened man. We had no idea what he would do: of how secure the Bawas were of his loyalties, or whether he might seek revenge for some past slight by revealing their whereabouts. If he did; both houses would burn.

Although stuttering in terror, the cook held his own. Yes, he said, yes, his employers were Sikhs but they had left town: there was no one in the house. No, the house didn’t belong to them; they were renting from a Hindu.

He succeeded in persuading most of the thugs, but a few eyed the surrounding houses suspiciously. Some appeared at the steel gates in front of us, rattling the bars.

We went up and positioned ourselves at the gates. I remember a strange sense of disconnection as I walked down the driveway, as though I was watching myself from somewhere very distant.

We took hold of the gates and shouted back: Get away! You have no business here. There’s no one inside! The house is empty!

To my surprise, they began to drift away, one by one. Just before this, I had stepped into the house to see how Mrs. Sen and the Bawas were faring. The thugs were clearly audible in the lamplit drawing room; only a thin curtain shielded the interior from their view.

My memory of what I saw in the drawing room is uncannily vivid. Mrs. Sen had a slight smile on her face as she poured a cup of tea for Mr. Bawa. Beside her, Mrs. Bawa, in a firm, unwavering voice, was comparing the domestic-help situations in New Delhi and Manila.

I was awed by their courage.

The next morning, I heard about a protest that was being organized at the large compound of a relief agency. When I arrived, a meeting was already underway, a gathering of seventy or eighty people.

The mood was somber. Some of the people spoke of neighborhoods that had been taken over by vengeful mobs. They described countless murders – mainly by setting the victims alight – as well as terrible destruction: the burning of Sikh temples, the looting of Sikh schools, the razing of Sikh homes and shops. The violence was worse than I had imagined. It was decided that the most effective initial tactic would be to march into one of the badly affected neighborhoods and confront the rioters directly.

The group had grown a hundred and fifty men and women, among them Swami Agnivesh, a Hindu ascetic; Ravi Chopra, a scientist and environmentalist; and a handful of opposition politicians, including Chander Sekhar, who became Prime Minister for a brief period several years later.

The group was pitifully small by the standards of a city where crowds of several hundred thousand were routinely mustered for political rallies. Nevertheless the members rose to their feet and began to march.

Years before, I had read a passage by V.S. Naipaul, which had stayed with me ever since. I have never been able to find it again, so this account is from memory. In his incomparable prose Naipaul describes a demonstration. He is in a hotel room, somewhere in Africa or South America; he looks down and see people marching past. To his surprise, the sight fills him with an obscure longing, a kind of melancholy, he is aware of a wish to go out, to join, to merge his concerns with theirs. Yet he knows he never will; it is simply not in his nature to join crowds.

For many years, I read everything of Naipaul’s I could lay my hands on; I couldn’t have enough of him. I read him with the intimate, appalled attention that one reserves for one’s most skillful interlocutors. It was he who first made it possible for me to think of myself as a writer, working in English.

I remembered the passage because I believed that I, too, was not a joiner, and in Naipaul’s pitiless mirror I thought I had seen an aspect of myself rendered visible. Yet as this forlorn little group marched out of the shelter of the compound I did not hesitate for a moment: without a second thought, I joined.

The march headed first to Lajpat Nagar, a busy commercial area a mile or so away. I knew the area. Though it was in New Delhi, its streets resembled the older parts of the city, where small cramped shops tended to spill out into the footpaths.

We were shouting slogans as we marched: hoary Gandhian staples of peace and brotherhood from half a century before. Then, suddenly, we were confronted with a starkly familiar spectacle, an image of twentieth century urban horror: burned out cars, their ransacked interiors visible through smashed windows; debris and rubble everywhere. Blackened pots had been strewn along the street. A cinema had been gutted, and the charred faces of film stars stared out at us from half-burned posters.

As I think back to that march, my memory breaks down, details dissolve. I recently telephoned some friends who had been there. There memories are similar to mine in only one respect; they, too, clung to one scene while successfully ridding their minds of the rest.

The scene my memory preserved is of a moment when it seemed inevitable that we would be attacked.

Rounding a corner, we found ourselves facing a crowd that was larger and more determined-looking that any other crowds that we had encountered. On each previous occasion, we had prevailed by marching at the thugs and engaging them directly, in dialogues that turned quickly into extended shouting matches. In every instance, we had succeeded in facing them down. But this particular mob was intent on confrontation. As its members advanced on us, brandishing knives and steel rods, we stopped. Our voices grew louder as they came towards us; a kind of rapture descended on us, exhilaration in anticipation of a climax. We braced for the attack, leaning forward as though into a wind.

And then something happened that I have never completely understood. Nothing was said; there was no signal, nor was there any break in the rhythm of our chanting. But suddenly all women in our group – and the women made up more than half of the group’s numbers – stepped out and surrounded the men; their saris and kameezes became thin, fluttering barrier, a wall around us. They turned to face the approaching men, challenging them, daring them to attack.

The thugs took a few more steps toward us and then faltered, confused. A moment later, they were gone.

The march ended at the walled compound where it had started. In the next couple of hours, an organization was created, the Nagrik Ekta Manch, or Citizen’s Unity Front, and its work – to bring relief to the injured and the bereft, to shelter the homeless – began the next morning. Food and clothing were needed, and camps had to be established to accommodate the thousands of people with nowhere to sleep. And by the next day we were overwhelmed – literally. The large compound was crowded with vanloads of blankets, secondhand clothing, shoes and sacks of flour, sugar and tea. Previously hard-nosed unsentimental businessmen sent cars and trucks. There was barely room to move.

My own role in the Front was slight. For a few weeks, I worked with a team from Delhi University, distributing supplies in the slums and working-class neighborhoods that had been worst hit by the rioting. Then I returned to my desk.

In time, inevitably, most of the Front’s volunteers returned to their everyday lives. But some members – most notably the women involved in the running of refugee camps – continued to work for years afterward with Sikh women and children who had been rendered homeless. Jaya Jaitley, Lalita Ramdas, Veena Das, Mita Bose, Radha Kumar: these women, each one an accomplished professional, gave up years of their time to repair the enormous damage that had been done in a matter of two or three days.

The Front also formed a team to investigate the riots. I briefly considered joining, but then decided that an investigation would be a waste of time because the politicians capable of inciting violence were unlikely to heed a tiny group of concerned citizens.

I was wrong. A document eventually produced by this team – a slim pamphlet entitled Who Are the Guilty – has become a classic, a searing indictment of the politicians who encouraged the riots and the police who allowed the rioters to have their way.

Over the years the Indian government has compensated some of the survivors of the 1984 violence and resettled some of the homeless. One gap remains: to this day, no instigator of the riots has been charged. But the pressure on the government has never gone away, and it continues to grow: every year, the nails hammered in by that slim document dig just a little deeper.

That pamphlet and others that followed are testaments to the only humane possibility available to people who live in multi-ethnic, multi-religious societies like those of the Indian sub-continent. Human-rights documents such as Who Are the Guilty? are essential to the process of broadening civil institutions: they are weapons with which society asserts itself against a state that runs criminally amok, as the one did in Delhi in November of 1984.

It is heartening that sanity prevails today in Punjab. But not elsewhere. In Bombay, local government officials want to stop any public buildings from being painted green – a color associated with the Muslim religion. And hundreds of city’s Muslims have been deported from the city slums – in at least one case for committing an offense no graver than reading a Bengali newspaper. It is imperative that government insure that those who instigate mass violence do not go unpunished.

The Bosnian writer Dzevad Karahasan, in a remarkable essay called Literature and War (published last year in the collection Sarajevo, Exodus of a City), makes a startling connection between modern literary aestheticism and the contemporary world’s indifference to violence:

The decision to perceive literally everything as an aesthetic phenomenon – completely sidestepping questions about goodness and truth – is an artistic decision. That decision started in the realm of art, and went on to become characteristic of the contemporary world.

When I went back to my desk in November 1984, I found myself confronting decisions about writing that I had never faced before. How was I to write about what I had seen without reducing it to a mere spectacle?

My next novel was bound to be influenced by my experiences, but I could see no way of writing directly about those events without recreating them as a panorama of violence – “an aesthetic phenomenon,” as Karahasan was to call it. At the time, the idea seemed obscene and futile; of much greater importance were factual reports of the testimony of the victims. But these were already being done by people who were, I knew, more competent than I could be.

Within a few months, I started my novel, which I eventually called The Shadow Lines – a book that led me backward in time, to earlier memories of riots, ones witnessed in childhood. It became a book not about any one event but about the meaning of such events and their effects on the individuals who live through them.

And until now I have never really written about what I saw in November 1984. I am not alone: several others who took part in that march went on to publish books, yet nobody, so far as I know, has ever written about it except in the passing.

There are good reasons for this, not least the politics of the situation, which leave so little room for the writer. The [pogroms] were generated by a cycle of violence, involving [freedom fighters] in Punjab on the one hand, and the Indian government on the other. To write carelessly in such a way as to endorse repression, can add easily to the problem: in such incendiary circumstances, words cost lives, and it is only appropriate that those who deal in words should pay scrupulous attention to what they say. It is only appropriate that they should find themselves inhibited.

But there is also a simple explanation. Before I could set down a word, I had to resolve a dilemma, between being a writer and being a citizen. As a writer, I had only obvious subjects: the violence. From the news report, or the latest film or novel, we have come to expect the bloody detail or the elegantly staged conflagration that closes a chapter or effects a climax. But it is worth asking if the very obviousness of this subject arises out of out modern conventions of representations: within the dominant aesthetic of our time – the aesthetic of what Karahasan calls “indifference” – it is all too easy to present violence as an apocalyptic spectacle, while the resistance to it can as easily figure as mere sentimentality, or worse, as pathetic or absurd.

Writers don’t join crowds – Naipaul and so many others teach us that. But what do you do when the Constitutional authority fails to act. You join and in joining bear all the responsibility and obligations and guilt that joining represents. My experience of the violence was overwhelming and memorable of the resistance to it. When I think of the women staring down the mob, I am not filled with writerly wonder. I am reminded of my gratitude from being saved from injury. What I saw at firsthand – and not merely on that march but on the bus, in Hari’s house, in the huge compound filled with essential goods – was not the horror of violence but the affirmation of humanity: in each case, I witnessed the risks that perfectly ordinary people were willing to take for one another.

When I now read descriptions of troubled parts of the world, in which violence appears primordial and inevitable, a fate to which masses of people are largely resigned, I find myself asking: Is that all there was to it? Or is it possible that the authors of these descriptions failed to find a form – or a style or a voice of a plot – that could accommodate both violence and the civilized, willed response to it?

The truth is that the commonest response to violence is one of the repugnance, and that a significant number of people everywhere try to oppose it in whatever way they can. That these effects so rarely appear in accounts of violence is not surprising: they are too un-dramatic. For those who participate in them, they are often hard to write about for the very reasons that so long delayed my own account of 1984.

“Let us not fool ourselves,” Karahasan writes. “The world is written first – the Holy Books say that it was created in words and all that happens in it, happens in language first.”

It is when we think of the world the aesthetic of indifference might bring into being that we recognize the urgency of remembering the stories we have not written.

This article was originally published in The New Yorker in 1995.Nowhere else in the world did the year 1984 fulfill its apocalyptic portents as it did in India. Separatist violence in the Punjab, the military attack on the great Sikh temple of Amritsar; the assassination of the Prime Minister, Mrs. Indira Gandhi; riots in several cities; the gas disaster in Bhopal – the events followed relentlessly on each other. There were days in 1984 when it took courage to open the New Delhi papers in the morning.

Of the year’s many catastrophes, the sectarian violence following Mrs Gandhi’s death had the greatest effect on my life. Looking back, I see that the experiences of that period were profoundly important to my development as a writer; so much so that I have never attempted to write about them until now.

At that time, I was living in a part of New Delhi called Defence Colony – a neighborhood of large, labyrinthine houses, with little self-contained warrens of servants’ rooms tucked away on roof-tops and above garages. When I lived there, those rooms had come to house a floating population of the young and straitened journalists, copywriters, minor executives, and university people like myself. We battened upon this wealthy enclave like mites in a honeycomb, spreading from rooftop to rooftop. Our ramshackle lives curtailed from our landlords of chiffon-draped washing lines and thickets of TV serials.

I was twenty-eight. The city I considered home was Calcutta, but New Delhi was where I had spent all my adult life except for a few years in England and Egypt. I had returned to India two years before, upon completing a doctorate at Oxford, and recently found a teaching job at Delhi University. But it was in the privacy of my baking rooftop hutch that my real life was lived. I was writing my first novel, in the classic fashion, perched in garret.

On the morning of October 31, the day of Mrs. Gandhi’s death, I caught a bus to Delhi University, as usual, at about half past nine. From where I lived, it took an hour and half; a long commute, but not an exceptional one for New Delhi. The assassination had occurred shortly before, just a few miles away, but I had no knowledge of this when I boarded the bus. Nor did I notice anything untoward at any point during the ninety-minute journey. But the news, traveling by word of mouth, raced my bus to the university.

When I walked into the grounds, I saw not the usual boisterous, Frisbee-throwing crowd of students but a small group of people standing intently around transistor radio. A young man detached himself from one of the huddles and approached me, his mouth twisted into light tipped, knowing smile that seems always to accompany the gambit “Have you heard…?”

The campus was humming, he said. No one knew for sure, but it was being said that Mrs. Gandhi had been shot. The word was that she had been assassinated by two Sikh bodyguards, in revenge for her having sent troops to raid the Sikhs’ Golden Temple in Amritsar earlier that year.

Just before stepping into the lecture room, I heard a report on All India Radio, the national network: Mrs. Gandhi had been rushed to hospital after her attempted assassinations.

Nothing stopped: the momentum of the daily routine carried things forward. I went into a classroom and began my lecture, but not many students had shown up and those who had were distracted and distant; there was a lot of fidgeting.

Halfway through the class, I looked out through the room’s single, slit-like window. The sunlight lay bright on the lawn below and on the trees beyond. It was the time of year when Delhi was at its best, crisp and cool. Its abundant greenery freshly watered by the recently retreated monsoons, its skies washed sparkling clean. By the time I turned back, I had forgotten what I was saying and had to reach for my notes.

My unsteadiness surprised me. I was not an uncritical admirer of Mrs. Gandhi. Her brief period of semi-dictatorial rule in the mid-seventies was still alive in my memory.

The first reliable report of Mrs. Gandhi’s death was broadcast from Karachi, by Pakistan, at around 1:30 PM. On All India Radio regular broadcast had been replaced by music.

I left the university in the late afternoon with a friend, Hari Sen, who lived at the other end of the city. I needed to make a long-distance call, and he had offered to let me use his family telephone.

To get to Hari’s house we had to change buses at Connaught Place, that elegant circular arcade that lies at the geographical heart of Delhi, linking the old city with the new. As the bus swung around the periphery of the arcade, I noticed that the shops, stalls, and eteries were beginning to shut down, even though it was still afternoon.

Our next bus was not quite full, which was unusual. Just as it was pulling out, a man ran out of the office and jumped on. He was middle-aged and dressed in shirt and trousers, evidently an employee in one of the government buildings. He was a Sikh, but I scarcely noticed this at the time.

He probably jumped on without giving the matter any thought, this being his regular, daily bus. But, as it happened, on this day no choice could have been more unfortunate, for the route of the bus went past the hospital where Indira Gandhi’s body then lay. Certain loyalists in her party had begun inciting the crowds gathered there to seek revenge. The motorcade of Giani Zail Singh, the President of the Republic, a Sikh, had already been attacked by a mob.

None of this was known to us then, and we would never have suspected it: violence had never been directed at the Sikhs in Delhi.

As the bus made its way down New Delhi’s broad, tree-lined avenues, official-looking cars, with outriders and escorts, overtook us, speeding toward the hospital. As we drew nearer, it became evident that a large number of people had gathered there. But this was no ordinary crowd: it seemed to consist of red-eyed young men in half-buttoned shirts. It was now that I noticed that my Sikh fellow-passenger was showing signs of anxiety, sometimes standing up to look out, sometimes glancing out the door. It was too late to get off the bus; thugs were everywhere.

The bands of young men grew more and more menacing as we approached the hospital. There was a watchfulness about them; some were armed with steel rods and bicycle chains; others had fanned out across the busy road and were stopping cars and buses.

A stout woman in sari sitting across aisle from me was the first to understand what was going on. Rising to her feet, she gestured urgently at the Sikh, who was sitting hunched in his seat. She hissed at him in Hindi, telling him to get down and keep out of sight.

The man started in surprise and squeezed himself into the narrow footspace between the seats. Minutes later, our bus was intercepted by a group of young men dressed in bright, sharp synthetics. Several had bicycle chains wrapped around their wrists. They ran along beside the bus as it slowed to a halt. We heard them call out to the driver through the open door, asking if there were any Sikhs in the bus.

The driver shook his head. No, he said, there were no Sikhs in the bus.

A few rows ahead of me, the crouching turbaned figure had gone completely still.

Outside, some of the young men were jumping up to look through the windows, asking if there were any Sikhs in the bus. There was no anger in their voices; that was the most chilling thing of all.

No, someone said, and immediately other voices picked up the refrain. Soon all the passengers were shaking their heads and saying, no, no, let us go now, we have to get home.

Eventually, the thugs stepped back and waved us through.

Nobody said a word as we sped away down Ring Road.

Hari Sen lived in one of New Delhi’s recently developed residential colonies. It was called Safdarjang Enclave, and it was neatly and solidly middle-class, a neighborhood of aspirations rather than opulence. Like most such suburbs, the area had a mixed population: Sikhs were well represented.

A long street ran from end to end of the neighborhood, like the spine of a comb, with parallel side streets running off it. Hari lived at the end of one of those streets, in a fairly typical, big, one-storey bunglow. The house next door, however, was much grander and uncharacteristically daring in design. An angular structure, it was perched rakishly on stilts. Mr. Bawa, the owner, was an elderly Sikh who had spent a long time abroad, working with various international organizations. For several years, he had resided in Southeast Asia; thus the stilts.

Hari lived with his family in a household so large and eccentric that it had come to be known among his friends as Macondo, after Gabriel Garcia Marquez’s magical village. On this occasion, however, only his mother and teenage sister were at home. I decided to stay over.

It was a bright morning. When I stepped into the sunshine, I came upon a sight that I could never have imagined. In every direction, columns of smoke rose slowly into a limpid sky. Sikh houses and businesses were burning. The fires were so carefully targeted that they created an effect quite different from that of a general conflagration: it was like looking upward into the vault of some vast pillared hall.

The columns of smoke increased in number even as I stood outside watching. Some fires were burning a short distance away. I spoke to a passerby and learned that several nearby Sikh houses had been looted and set on fire that morning. The mob had started at the far end of the colony and was working its way in our direction. Hindus or Muslims who had sheltered Sikhs were also being attacked; their houses too were being looted and burned.

It was still and quite, eerily so. The usual sounds of rush-hour traffic were absent. But every so often we heard a speeding car or a motorcycle on the main street. Later, we discovered that these mysterious speeding vehicles were instrumental in directing the carnage that was taking place. Protected by certain politicians, “organizers” were zooming around the city, assembling the mobs and transporting them to Sikh-owned houses and shops.

Apparently, the transportation was provided free. A civil-rights report published shortly afterward stated that this phase of violence “began with the arrival of groups of armed people in tempo vans, scooters, motorcycles or trucks,” and went on to say,

With cans of petrol they went around the localities and systematically set fire to Sikh-houses, shops and Gurdwaras…the targets were primarily young Sikhs. They were dragged out, beaten up and then burned alive…In all the affected spots, a calculated attempt to terrorize the people was evident in the common tendency among the assailants to burn alive Sikhs on public roads.

Fire was everywhere; it was the day’s motif. Throughout the city, Sikh houses were being looted and then set on fire, often with their occupants still inside.

A survivor – a woman who lost her husband and three sons – offered the following account to Veena Das, a Delhi sociologist:

Some people, the neighbors, one of my relatives, said it would be better if we hid in an abandoned house nearby. So my husband took our three sons and hid there. We locked the house from outside, but there was treachery in people’s hearts. Someone must have told the crowd. They baited him to come out. Then they poured kerosene on that house. They burnt them alive. When I went there that night, the bodies of my sons were on the loft – huddled together.

Over the next few days, some 2,500 people died in Delhi alone. Thousands more died in other cities. The total death toll will never be known. The dead were overwhelmingly Sikh men. Entire neighborhoods were gutted; tens of thousands of people were left homeless.

Like many other members of my generation, I grew up believing that mass slaughter of the kind that accompanied the Partition of India and Pakistan, in 1947, could never happen again. But that morning in the city of Delhi, the violence had reached the same level of intensity.

As Hari and I stood staring into the smoke-streaked sky, Mrs. Sen, Hari’s mother, was thinking of matters closer at hand. She was about fifty, a tall, graceful woman with a gentle, soft-spoken manner. In an understated way, she was also deeply religious, a devout Hindu. When she heard what was happening, she picked up the phone and called Mr. And Mrs. Bawa, the elderly Sikh couple next door, to let them know that they were welcome to come over. She met with unexpected response: an awkward silence. Mrs. Bawa thought she was joking, and wasn’t sure whether to be amused or not.

Toward midday, Mrs. Sen received a phone call: the mob was now in the immediate neighborhood, advancing systematically from street to street. Hari decided that it was time to go over and have a talk with the Bawas. I went along.

Mr. Bawa proved to be small, slight man. Although he was casually dressed, his turban was neatly tied and his beard was carefully combed and bound. He was puzzled by our visit. After a polite greeting, he asked what he could do for us. It fell to Hari to explain.

Mr. Bawa had heard about Indira’s assassination, of course, and he knew there had been some trouble. But he could not understand why these “disturbances” should impinge on him or his wife. Not only was his commitment to India and the Indian state absolute but it was evident from his bearing that he belonged to the country’s ruling elite.

How do you explain to someone who has spent a lifetime cocooned in privilege that a potentially terminal rent has appeared in the wrappings? We found ourselves faltering. Mr. Bawa could not bring himself to believe that a mob might attack him.

By the time we left, it was Mr. Bawa who was mouthing reassurances. He sent us off with jovial pats on our backs. He did not actually say “Buck up”, but his manner said it for him.

We were confident that the government would soon act to stop the violence. In India, there is a drill associated with civil disturbances: a curfew is declared; paramilitary units are deployed; in extreme cases the army marches to the stricken areas. No city in India is better equipped to perform this drill than New Delhi, with its huge security apparatus. We learned later that in some cities – Calcutta, for example, the state authorities did act promptly to prevent violence. But in New Delhi – and much of North India – [days] followed without a response.

Every few minutes we turned to the radio, hoping to hear that the Army had been ordered out. All we heard was mournful music and descriptions of Mrs. Gandhi’s lying in state; of coming and goings of dignitaries, foreign and national. The bulletins could have been messages from another planet.

As the afternoon progressed, we continued to hear reports of the mob’s steady advance. Before long, it had reached the next alley: we could hear the voices; the smoke was everywhere. There was still no sign of Army or police.

Hari again called Mr. Bawa, and now the flames visible from his windows, he was more receptive. He agreed to come over with his wife, just for a short while. But there was a problem: How? The two properties were separated by a shoulder -high wall, so it was impossible to walk from one house to the other except along the street.

I spotted a few thugs already at the end of the street. We could hear the occasional motorcycle, cruising slowly up and down. The Bawas could not risk stepping out in the street. They would be seen: the sun had dipped low in the sky, but it was still light. Mr. Bawa balked at the thought of climbing over the wall: it seemed an inseparable obstacle at his age. But eventually Hari persuaded him to try.

We went to wait for them at the back of the Sen’s house – in a spot that was well sheltered from the street. The mob seemed terrifyingly close, the Bawas reckless in their tardiness. A long time appeared before the elderly couple finally appeared, hurrying towards us.

Mr. Bawa had changed before leaving the house: he was neatly dressed, dapper, even a blazer and cravat. Mrs. Bawa dressed in salwar and kameez. Their cook was with them, and it was with his assistance that they made it over the wall. The cook, who was Hindu, then returned to the house to stand guard.

Hari led the Bawas into the drawing room, where Mrs. Sen was waiting dressed in chiffon sari. The room was large and well appointed, its walls hung with a rare and beautiful set of miniatures. With the curtains now drawn and the lamps lit, it was warm and welcoming. But all that lay between us and the mob in the street was a row of curtained French windows and a garden wall.

Mrs. Sen greeted the elderly couple with folded hands as they came in. The three seated themselves in the intimate circle, and soon a silver tea tray appeared. Instantly, all constraint evaporated, and, to the tinkling of porcelain, the conversation turned to the staples of New Delhi drawing-room chatter.

I could not bring myself to sit down. I stood in the corridor, distracted, looking outside through the front entrance.

A couple of scouts on motorcycles had drawn up next door. They had dismounted and were inspecting the house, walking in among the concrete stilts, looking up into the house. Somehow, they got wind of the cook’s presence and called him out.

The cook was very frightened. He was surrounded by thugs thrusting knives in his face and shouting questions. It was dark, and some were carrying kerosene torches. Wasn’t it true, they shouted, that his employers were Sikhs.

Where were they? Were they hiding inside? Who owned the house – Hindus or Sikhs? Hari and I hid behind the wall and listened to the interrogation. Our fates depended on this lone, frightened man. We had no idea what he would do: of how secure the Bawas were of his loyalties, or whether he might seek revenge for some past slight by revealing their whereabouts. If he did; both houses would burn.

Although stuttering in terror, the cook held his own. Yes, he said, yes, his employers were Sikhs but they had left town: there was no one in the house. No, the house didn’t belong to them; they were renting from a Hindu.

He succeeded in persuading most of the thugs, but a few eyed the surrounding houses suspiciously. Some appeared at the steel gates in front of us, rattling the bars.

We went up and positioned ourselves at the gates. I remember a strange sense of disconnection as I walked down the driveway, as though I was watching myself from somewhere very distant.

We took hold of the gates and shouted back: Get away! You have no business here. There’s no one inside! The house is empty!

To my surprise, they began to drift away, one by one. Just before this, I had stepped into the house to see how Mrs. Sen and the Bawas were faring. The thugs were clearly audible in the lamplit drawing room; only a thin curtain shielded the interior from their view.

My memory of what I saw in the drawing room is uncannily vivid. Mrs. Sen had a slight smile on her face as she poured a cup of tea for Mr. Bawa. Beside her, Mrs. Bawa, in a firm, unwavering voice, was comparing the domestic-help situations in New Delhi and Manila.

I was awed by their courage.

The next morning, I heard about a protest that was being organized at the large compound of a relief agency. When I arrived, a meeting was already underway, a gathering of seventy or eighty people.

The mood was somber. Some of the people spoke of neighborhoods that had been taken over by vengeful mobs. They described countless murders – mainly by setting the victims alight – as well as terrible destruction: the burning of Sikh temples, the looting of Sikh schools, the razing of Sikh homes and shops. The violence was worse than I had imagined. It was decided that the most effective initial tactic would be to march into one of the badly affected neighborhoods and confront the rioters directly.

The group had grown a hundred and fifty men and women, among them Swami Agnivesh, a Hindu ascetic; Ravi Chopra, a scientist and environmentalist; and a handful of opposition politicians, including Chander Sekhar, who became Prime Minister for a brief period several years later.

The group was pitifully small by the standards of a city where crowds of several hundred thousand were routinely mustered for political rallies. Nevertheless the members rose to their feet and began to march.

Years before, I had read a passage by V.S. Naipaul, which had stayed with me ever since. I have never been able to find it again, so this account is from memory. In his incomparable prose Naipaul describes a demonstration. He is in a hotel room, somewhere in Africa or South America; he looks down and see people marching past. To his surprise, the sight fills him with an obscure longing, a kind of melancholy, he is aware of a wish to go out, to join, to merge his concerns with theirs. Yet he knows he never will; it is simply not in his nature to join crowds.

For many years, I read everything of Naipaul’s I could lay my hands on; I couldn’t have enough of him. I read him with the intimate, appalled attention that one reserves for one’s most skillful interlocutors. It was he who first made it possible for me to think of myself as a writer, working in English.

I remembered the passage because I believed that I, too, was not a joiner, and in Naipaul’s pitiless mirror I thought I had seen an aspect of myself rendered visible. Yet as this forlorn little group marched out of the shelter of the compound I did not hesitate for a moment: without a second thought, I joined.

The march headed first to Lajpat Nagar, a busy commercial area a mile or so away. I knew the area. Though it was in New Delhi, its streets resembled the older parts of the city, where small cramped shops tended to spill out into the footpaths.

We were shouting slogans as we marched: hoary Gandhian staples of peace and brotherhood from half a century before. Then, suddenly, we were confronted with a starkly familiar spectacle, an image of twentieth century urban horror: burned out cars, their ransacked interiors visible through smashed windows; debris and rubble everywhere. Blackened pots had been strewn along the street. A cinema had been gutted, and the charred faces of film stars stared out at us from half-burned posters.

As I think back to that march, my memory breaks down, details dissolve. I recently telephoned some friends who had been there. There memories are similar to mine in only one respect; they, too, clung to one scene while successfully ridding their minds of the rest.

The scene my memory preserved is of a moment when it seemed inevitable that we would be attacked.

Rounding a corner, we found ourselves facing a crowd that was larger and more determined-looking that any other crowds that we had encountered. On each previous occasion, we had prevailed by marching at the thugs and engaging them directly, in dialogues that turned quickly into extended shouting matches. In every instance, we had succeeded in facing them down. But this particular mob was intent on confrontation. As its members advanced on us, brandishing knives and steel rods, we stopped. Our voices grew louder as they came towards us; a kind of rapture descended on us, exhilaration in anticipation of a climax. We braced for the attack, leaning forward as though into a wind.

And then something happened that I have never completely understood. Nothing was said; there was no signal, nor was there any break in the rhythm of our chanting. But suddenly all women in our group – and the women made up more than half of the group’s numbers – stepped out and surrounded the men; their saris and kameezes became thin, fluttering barrier, a wall around us. They turned to face the approaching men, challenging them, daring them to attack.

The thugs took a few more steps toward us and then faltered, confused. A moment later, they were gone.

The march ended at the walled compound where it had started. In the next couple of hours, an organization was created, the Nagrik Ekta Manch, or Citizen’s Unity Front, and its work – to bring relief to the injured and the bereft, to shelter the homeless – began the next morning. Food and clothing were needed, and camps had to be established to accommodate the thousands of people with nowhere to sleep. And by the next day we were overwhelmed – literally. The large compound was crowded with vanloads of blankets, secondhand clothing, shoes and sacks of flour, sugar and tea. Previously hard-nosed unsentimental businessmen sent cars and trucks. There was barely room to move.

My own role in the Front was slight. For a few weeks, I worked with a team from Delhi University, distributing supplies in the slums and working-class neighborhoods that had been worst hit by the rioting. Then I returned to my desk.

In time, inevitably, most of the Front’s volunteers returned to their everyday lives. But some members – most notably the women involved in the running of refugee camps – continued to work for years afterward with Sikh women and children who had been rendered homeless. Jaya Jaitley, Lalita Ramdas, Veena Das, Mita Bose, Radha Kumar: these women, each one an accomplished professional, gave up years of their time to repair the enormous damage that had been done in a matter of two or three days.

The Front also formed a team to investigate the riots. I briefly considered joining, but then decided that an investigation would be a waste of time because the politicians capable of inciting violence were unlikely to heed a tiny group of concerned citizens.

I was wrong. A document eventually produced by this team – a slim pamphlet entitled Who Are the Guilty – has become a classic, a searing indictment of the politicians who encouraged the riots and the police who allowed the rioters to have their way.

Over the years the Indian government has compensated some of the survivors of the 1984 violence and resettled some of the homeless. One gap remains: to this day, no instigator of the riots has been charged. But the pressure on the government has never gone away, and it continues to grow: every year, the nails hammered in by that slim document dig just a little deeper.

That pamphlet and others that followed are testaments to the only humane possibility available to people who live in multi-ethnic, multi-religious societies like those of the Indian sub-continent. Human-rights documents such as Who Are the Guilty? are essential to the process of broadening civil institutions: they are weapons with which society asserts itself against a state that runs criminally amok, as the one did in Delhi in November of 1984.

It is heartening that sanity prevails today in Punjab. But not elsewhere. In Bombay, local government officials want to stop any public buildings from being painted green – a color associated with the Muslim religion. And hundreds of city’s Muslims have been deported from the city slums – in at least one case for committing an offense no graver than reading a Bengali newspaper. It is imperative that government insure that those who instigate mass violence do not go unpunished.

The Bosnian writer Dzevad Karahasan, in a remarkable essay called Literature and War (published last year in the collection Sarajevo, Exodus of a City), makes a startling connection between modern literary aestheticism and the contemporary world’s indifference to violence:

The decision to perceive literally everything as an aesthetic phenomenon – completely sidestepping questions about goodness and truth – is an artistic decision. That decision started in the realm of art, and went on to become characteristic of the contemporary world.

When I went back to my desk in November 1984, I found myself confronting decisions about writing that I had never faced before. How was I to write about what I had seen without reducing it to a mere spectacle?

My next novel was bound to be influenced by my experiences, but I could see no way of writing directly about those events without recreating them as a panorama of violence – “an aesthetic phenomenon,” as Karahasan was to call it. At the time, the idea seemed obscene and futile; of much greater importance were factual reports of the testimony of the victims. But these were already being done by people who were, I knew, more competent than I could be.

Within a few months, I started my novel, which I eventually called The Shadow Lines – a book that led me backward in time, to earlier memories of riots, ones witnessed in childhood. It became a book not about any one event but about the meaning of such events and their effects on the individuals who live through them.

And until now I have never really written about what I saw in November 1984. I am not alone: several others who took part in that march went on to publish books, yet nobody, so far as I know, has ever written about it except in the passing.

There are good reasons for this, not least the politics of the situation, which leave so little room for the writer. The [pogroms] were generated by a cycle of violence, involving [freedom fighters] in Punjab on the one hand, and the Indian government on the other. To write carelessly in such a way as to endorse repression, can add easily to the problem: in such incendiary circumstances, words cost lives, and it is only appropriate that those who deal in words should pay scrupulous attention to what they say. It is only appropriate that they should find themselves inhibited.

But there is also a simple explanation. Before I could set down a word, I had to resolve a dilemma, between being a writer and being a citizen. As a writer, I had only obvious subjects: the violence. From the news report, or the latest film or novel, we have come to expect the bloody detail or the elegantly staged conflagration that closes a chapter or effects a climax. But it is worth asking if the very obviousness of this subject arises out of out modern conventions of representations: within the dominant aesthetic of our time – the aesthetic of what Karahasan calls “indifference” – it is all too easy to present violence as an apocalyptic spectacle, while the resistance to it can as easily figure as mere sentimentality, or worse, as pathetic or absurd.

Writers don’t join crowds – Naipaul and so many others teach us that. But what do you do when the Constitutional authority fails to act. You join and in joining bear all the responsibility and obligations and guilt that joining represents. My experience of the violence was overwhelming and memorable of the resistance to it. When I think of the women staring down the mob, I am not filled with writerly wonder. I am reminded of my gratitude from being saved from injury. What I saw at firsthand – and not merely on that march but on the bus, in Hari’s house, in the huge compound filled with essential goods – was not the horror of violence but the affirmation of humanity: in each case, I witnessed the risks that perfectly ordinary people were willing to take for one another.

When I now read descriptions of troubled parts of the world, in which violence appears primordial and inevitable, a fate to which masses of people are largely resigned, I find myself asking: Is that all there was to it? Or is it possible that the authors of these descriptions failed to find a form – or a style or a voice of a plot – that could accommodate both violence and the civilized, willed response to it?

The truth is that the commonest response to violence is one of the repugnance, and that a significant number of people everywhere try to oppose it in whatever way they can. That these effects so rarely appear in accounts of violence is not surprising: they are too un-dramatic. For those who participate in them, they are often hard to write about for the very reasons that so long delayed my own account of 1984.

“Let us not fool ourselves,” Karahasan writes. “The world is written first – the Holy Books say that it was created in words and all that happens in it, happens in language first.”

It is when we think of the world the aesthetic of indifference might bring into being that we recognize the urgency of remembering the stories we have not written.

This article was originally published in The New Yorker in 1995.

Christmas in The West

Christmas in The West Christmas in America is an amalgamation of tradition and mythology. The holiday may or may not be religious in nature depending on who is doing the celebrating, and has become a very commercial event.

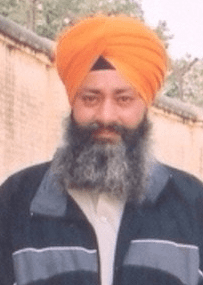

Christmas in America is an amalgamation of tradition and mythology. The holiday may or may not be religious in nature depending on who is doing the celebrating, and has become a very commercial event.  Bhai Gurbakhash Singh Khalsa is today’s hero of the Sikh freedom struggle who has energized and mobilized the freedom movement by demonstrating unprecedented determination and commitment in sacrificing himself for the release of Sikh freedom fighters who are still behind bars, even though their jail terms have been completed.

Bhai Gurbakhash Singh Khalsa is today’s hero of the Sikh freedom struggle who has energized and mobilized the freedom movement by demonstrating unprecedented determination and commitment in sacrificing himself for the release of Sikh freedom fighters who are still behind bars, even though their jail terms have been completed.

Akali Phoola Singh was born on January 14th 1761, in a village called Sarinh, which is in the present day district of Sangrur in Punjab. He is perhaps most famously known for his decision as the Jathedar of Akal Takhat Sahib, to whip Raja Ranjit Singh in front of the Akal Takhat after the Raja had married a Muslim woman and become a patit (apostate).

Akali Phoola Singh was born on January 14th 1761, in a village called Sarinh, which is in the present day district of Sangrur in Punjab. He is perhaps most famously known for his decision as the Jathedar of Akal Takhat Sahib, to whip Raja Ranjit Singh in front of the Akal Takhat after the Raja had married a Muslim woman and become a patit (apostate).